From rod types and weights, through myriad wet or dry lines, to an endless selection of flies catering to the most specific scenarios, fly fishers understand the concept of being selective. But selectivity at the scale of a day out on the water only has consequences for conservation at the most immediate level–when a fish is released with minimal harm.

But what about selectivity in the world of fish harvest? Selective harvest is the term used for this concept by governments. It’s a topic that has been discussed with little consequence for decades. A Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) policy first emerged in 2001 recognizing: “Because different species and stocks often mingle in the open ocean and river fisheries, fishers seeking stocks in greater abundance regularly catch less abundant or threatened fish stocks … a strategy to harvest abundances of large, healthy stocks of salmon of all species while ensuring conservation of smaller, threatened stocks. The answer, not just for salmon, but groundfish, invertebrates, seabirds, marine mammals, and all other species at risk of over-exploitation, is the widespread adoption of selective fishing techniques.” In other words, at this scale, selectivity matters to entire populations.

As evidenced by the 2023 Harvest Transformation policy, DFO is now promoting a more sophisticated approach to selective harvest. That sounds positive, but how does it affect fly fishers whose passion is anadromous steelhead and salmon? The answer lies in the overlap of run timing between highly prized sockeye (or lesser prized pink) with steelhead and some chinook. There are many fisheries intercepting co-migrating species; whether it’s commercial Seine fisheries at the mouth of a river or gill nets operating under Food, Social and Ceremonial rights along major rivers. Both kill non-target steelhead and salmon, some of whom come from endangered populations. As returns dwindle, the effect of non-selective fishing practices becomes noticeably outdated and the impacts increasingly dire.

In a 2022 letter, the Province told DFO, “we remain very concerned about the impact of (non-target) by-catch on Interior Fraser River steelhead populations which are of Extreme Conservation Concern … It is critical that the declining abundance of northern steelhead is addressed immediately and by all management agencies to avoid a similarly disastrous scenario for Skeena steelhead as is now occurring for Interior Fraser Steelhead”. (Re)enter selective harvest, which “targets species of salmon while reducing by-catch mortality and protecting threatened steelhead and salmon”, says Janvier Doire, of Skeena Fisheries Commission.

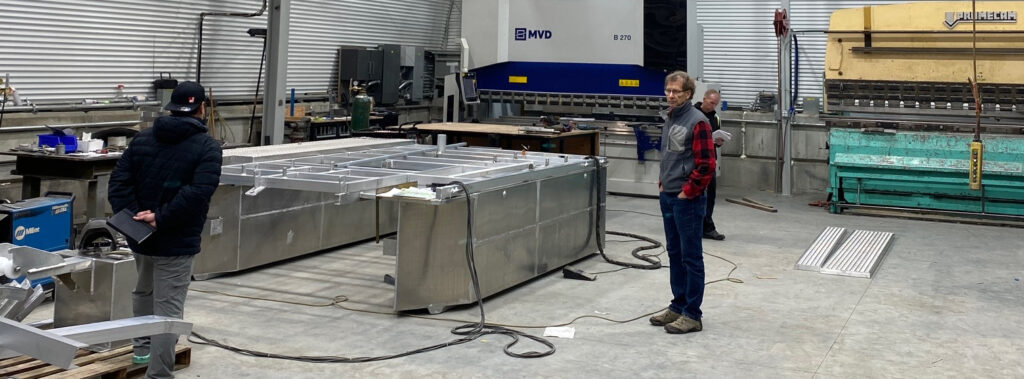

Historic selective harvest practices of First Nations are returning in many forms: weirs, traps, dip nets, beach seines, reef nets and fish wheels, several of which are in operation today in BC. Doire continues: “By promoting selective fishing and reducing by-catch mortality, fish traps may well be part of the future to help protect and restore BC’s wild salmon and steelhead populations.” In an 2020 article Indigenous Systems of Management for Culturally and Ecologically Resilient Pacific Salmon, the authors suggest “Indigenous management of salmon, including selective fishing technologies, harvest practices, and governance grounded in multigenerational place-based knowledge … showcase pathways for sustained productivity and resilience in contemporary salmon fisheries”

The BC Federation of Fly Fishers is actively promoting the concept of responsible selective harvest as a policy solution to what may be the most serious challenge to sustaining BC’s Fraser and Skeena steelhead today. Learn more, encourage others, write government, and join in our advocacy movement to bring about this change!